Modern Masters of Jiki Shinkage-ryū

Updated:

Examining the connections between Sakakibara Kenkichi, Yamada Jirokichi, Kawashima Takashi, and Ōnishi Hidetaka

In 2025 I took some time to read Japanese language sources on Jiki Shinkage-ryū, and have written two summaries. The first is focused on Ogasawara Genshinsai, the fourth lineal head of what is today called Kashima-shinden Jiki Shinkage-ryū:

I then arranged available information I have drawn from Japanese language Jiki Shinkage-ryū, Kendō, and Kyudō histories of the twentieth century centered around the practice and teaching of four masters of Kashima-shinden Jiki Shinkage-ryū Odani-ha — Sakakibara Kenkichi, Yamada Jirokichi, Kawashima Takashi, and Ōnishi Hidetaka:

There is a fair amount of available information on the transmission of Jiki Shinkage-ryū Odani-ha kenjutsu in the late 19th and early 20th century in Japanese. In this essay, discussion centers around the teaching and relationships of four modern masters of the art. Jiki Shinkage-ryū, which was quite small at its inception and influenced more than one deep tradition over time, grew in the late Edo period to a very large size, where some of its original character was very likely lost in its most prolific branches of practice but an essential character many advanced kenshi found inspiring survived.

Sakakibara Kenkichi

The lineage of what is considered today the main line of Jiki Shinkage-ryū was very likely almost broken with the death of its 14th headmaster, Sakakibara Kenkichi. Sakakibara had issued several upper-level licenses in the art over time, but the most likely successor being fellow student of Otani Nobutomo named Shimada Toranosuke (1810–1864) who predeceased him. The late Iwasa Minoru in the Japanese magazine titled “Budo” viewed Sakakibara’s death as having broken the main Seito-ha line of the art; in the discussion below I take a more charitable view but still tend to use the term Odani-ha instead of Seito-ha for consistency.

Sakakibara's later life dōjō was famous for sparring and would only do traditional kata practice periodically, or at the very least emphasized it much less than they did jigeiko and shiai. Namiki Yasushi maintained that Jikishinkage-ryū had practices such as yawara and sojutsu that were were lost over time — telling, because Matsumoto Bizen no Kami, the founder of Jiki Shinkage-ryū, was most famously reported as a spearman and other lines of Shinkage-ryū maintain sojutsu at their upper levels of training. However, this loss may be explained not by neglect of some kind but more likely the specialization that occurred during the Edo period. For example, Odani Nobutomo was also licensed in Hozoin-ryū sojutsu while Shimada Toranosuke practiced Kitō-ryū jujutsu.

Yamada Jirokichi

Yamada Jirokichi (1863-1930) was an important figure both in the rise and development of kendō and the preservation of aspects of Jiki Shinkage-ryū as Sakakibara’s successor. It is said by Ishigaki and Iwasa that Yamada Jirokichi had to go to another line, the Fujikawa-ha, to learn the upper-level kata after Sakakibara's passing – Sakakibara died when Yamada was only 31 years of age. So, some of what is done in what is called the mainline or standard line of Kashima-shinden Jiki Shinkage-ryū practice today might be drawn from that Fujikawa-ha kata practice and possibly not Sakakibara's complete transmission of the Odani-ha.

Sakakibara, who was bodyguard of the last Tokugawa shogun and keeper of Edo castle, was a famous kenshi and deserving of much praise for his efforts to maintain a practice of swordsmanship relevant to Japanese society as it modernized. A peculiarity of the historical record is while there are stories maintained of Sakakibara providing Yamada an upper-level license in the form of a densho his teacher had provided him, Yamada's menkyo-kaiden in Jikishinkage-ryū according to Iwasa Minoru was stamped by Sakakibara's widow after Sakakibara died. It is unclear why both Iwasa and Ishigaki would focus on those irregularities in their writing.

According to Ishigaki, Yamada’s document has siddham characters towards it end reading kanman – a reference to intuition and fudoshin – used in the Fujiwara line instead of the siddham characters for A-Un used in the Odani-ha Sakakibara was part of. So, Yamada potentially copied from a Fujikawa example he found or paid quiet homage to where he completed his training under Saito Akinobu between 1909 and 1911, after Sakakibara's passing.

その斎藤明信から山田次朗吉が明治四十二年前後の 二年間に渉って法定四本之形などの奥儀を受けたのは 事実のことだから、彼はこの時受けた伝書中のカンマ ソの文字を榊原伝も同様と思い込んでしまったのでは ないだろうか — 小笠原源信斎『真之心陰兵法目録』寛文 10 年, 真之心陰兵法免状』寛文 13 年,小田原市立図書館蔵

Unless this is the copy Sakakibara provided and those characters change from time to time. In any case, Yamada Jirokichi was a great teacher, practitioner, and scholar of kendō— his books on the history of Japanese swordsmanship, both older styles and kendō, seem monumental in their scope. He wanted to increase the martial vigor of kendō instruction as it spread, and associated to his efforts and those of others, practice of the foundational kata of Jiki Shinkage-ryū was introduced to several kendō clubs. Jiki Shinkage-ryū documents contain the following passage:

反面、己自身にも虚実二気が生じることを忘れては ならない。その為には己の息の出し入れを察知されな いよう充分心掛け、平素から荒い呼気を押え、7の気 とウンの気が一つに合い和する修練を積まねばいけな

We must not forget that we also have two energies, real and false. We must be careful not to let others notice when we breathe in and out, and we must practice suppressing rough breathing and harmonizing the seven energies and the a-un energies into one.

Given the teaching above, I wonder if the loud kiai and ibuki style breathing found in the main lines of contemporary Jiki Shinkage-ryū were actually a later invention, that became out of balance over time in a desire to instill proper fighting spirit to a very large audience – first at Sakakibara's dōjō and then later the many people learning kendō in the early twentieth century.

One cannot underestimate the impact four events had on Japanese budō. First, the banning of the wearing of swords, effectively abolishing the samurai caste. Second, the forced separation of Buddhism from Shinto, damaging the psycho-spiritual underpinnings many forms of budō leveraged. Third, the quick modernization of Japan. Fourth, the defeat of Japan at the end of World War II and the ban on the practice of martial arts. Historians can provide long analyses of each of these events and their circumstance, effects, and outcomes, but here I will focus much more narrowly on the impact modernization had on Jiki Shinkage-ryū. Successive inheritors of the art had extensive periods of time where they were not training in Jiki Shinkage-ryū, but I will address that below.

Kawashima Takashi

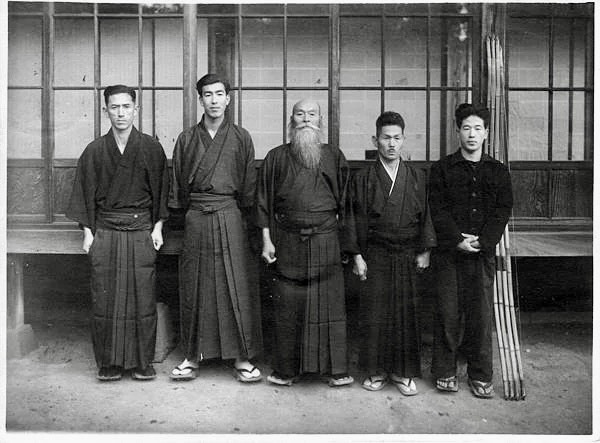

Kawashima Takashi (Yao) (川島堯, 1883-1957) and Ōnishi Hidetaka (大西英隆, 1906–1966) and both trained in Jiki Shinkage-ryū under Yamada Jirokichi. About Kawashima it is known from kyudō researchers that:

In 1904, Kawashima joined the navy and participated in the Russo-Japanese War. He moved to Taiwan in 1910 at the age of 27 and there became a kyudō disciple of Sakai Hitaro (酒井彦太郎; 1867-1951) in Heki-ryu Sekka-ha kyudō. In 1925, Kawashima was asked by Yamada Jirokichi to be his successor, but he declined. In 1927, he took employment as an educator in Tainan Commercial High School. In 1930, he worked with the Police Affairs Department and opened a kyudō school called the Mishinkan. In 1931, he was declared a kyudō master, following his teacher. In 1952 he published, "Kyudō Retrospective," in Kamisakai Village, Chiba Prefecture. He later died on August 17, 1957. He was buried in Yamamu City, Chiba Prefecture with the posthumous name "Butokuin Kyuu no Yoshisei." There is a monument to Kawashima at Kotohira Shrine in Chiba.

The Jikishinkage-ryū Hyakurenkai describe the event as Kawashima having declined to be Yamada’s successor due to guilt he felt from actions he undertook in Taiwan, saying he had killed many people. The circumstances of those actions are not listed. However, he then went on to teach at a high school and open a kyudō school, which he was active in until his death. There is likely something much more to his early story in Taiwan between 1910 and 1925 that is not currently available to researchers.

Ōnishi wrote of Kawashima:

Mr. Kawashima Takashi, a kendō master in Tainan, had a great reputation as the best swordsman in Taiwan, and had mastered both kendō and Kyudō. However, he was burning with a desire to further master the mysteries of kendō. By chance, he heard rumors about Mr. Yamada Jirokichi, a kendō master at Tokyo University of Commerce who was also from Chiba Prefecture, from Mr. Kojima Masashi, a kendō instructor at the Hualien Port Authority at the Taipei branch of the Dai Nippon Butokukai. He decided that this was the great teacher he should be taught by.

This indicates Kawashima returned to Japan to train with Yamada Jirokichi — it is unclear how many times and for how long.

Ōnishi Hidetaka

Ōnishi was captain of the Kendō Club of Hitosubashi University and underwent a seven-day ordeal practicing Hōjō 100 times a day for seven days at a mountain temple in Yamanishi prefecture before receiving his final license from Yamada Jirokichi. Intense mountain training of Hōjō was also undertaken at Mt. Kurotaki Fudo-ji Temple in Gunma inspired by a retreat conducted by Amano Hachiro of the Shogitai, a famous Jikishinkage-ryū practitioner.Ōnishi recounts the following description of his own meeting with Yamada:

In May 1925, when I participated in the Kyoto Butokukai Headquarters Tournament, I wanted to receive instruction from Yamada Sensei, so I went to Tokyo accompanied by two of my students and immediately visited him at his residence in Okachimachi, Shitaya, without any prior introduction. Yamada Sensei opened the shoji screen of the room on his left side to welcome this unknown guest, saying,

"I have been waiting for you this morning. When I washed my face and bowed to the sun, I sensed that three unusual guests were coming from far to the south. Please come in." Upon being greeted by their warm and sincere demeanor, as if they were old acquaintances, and with no estrangement whatsoever, the man said he felt an indescribable sense of nostalgia, as if struck by a mysterious electric current.

The disciple who was accompanying him hesitated, thinking that Yamada Sensei had mistaken him for someone else, but was urged repeatedly by the Sensei to enter the tatami room. As soon as he sat down, he was surprised to be served tea and snacks that had already been prepared for all four people.

When we met with Professor Yamada during our student days, there were many times when we had questions and wanted to ask him, but he would carefully explain them to us without us even having a chance to ask.

Yamada Jirokichi died in December 1929. Ōnishi writes:

On November 23, 1929, just 40 days before Yamada Sensei passed away, Yamada Sensei and I performed the habiki kata at the Hitotsubashi Dōjō. That day was the Hitotsubashi Kendō Club's Kendō Tournament, and many instructors, as well as kendō players from universities throughout Tokyo, attended. The packed hall was intoxicated for a moment by the spirit and flash of light, and we all forgot ourselves as we watched. Sensei demonstrated to the fullest the quintessence of Japanese martial arts, a masterful technique that unites stillness and movement. His tremendous spirit overwhelmed the packed hall, and his majesty was so great that words are lacking to describe it. This sensitivity and courage are great mental strengths that can be applied to all kinds of everyday situations.

One item we can deduce from the above is that Ōnishi trained under Yamada Jirokichi in Jikishinkage-ryū kata for an intense period of 4 years, from 1925 to 1929, which had a profound effect on him then and later in life. Kawashima also trained under Yamada Jirokichi for what was likely a similarly brief but intense period. I think an important difference between training in the 1920’s versus today is that these masters were already extremely proficient at the kendō of that period before training in Jikishinkage-ryū. Jikishinkage-ryū was viewed as a finishing school of sorts, where people would learn Hōjō and other parts of its curriculum to improve their already high-level swordsmanship.

It was thirty-four years later in 1963, after the death of Kawashima, that Ōnishi Hidetaka declared himself to the be the successor to Yamada Jirokichi as 17th generation headmaster of the art, retroactively naming the deceased Kawashima as its 16th generation headmaster and revived the school. I suppose Kawashima was so well respected by his contemporaries in the art, they went without having another headmaster in his stead for many years, whether he regarded himself as such. Or they were so impressed by his kendō that it felt appropriate. Or, the idea of a headmaster was not necessary, as each person was already an advanced kendōka who viewed their Jikishinkage-ryū practice as the culmination of their training – training in Sakakibara’s art with similar privations such as intense hojo practice famous samurai conducted being a modern-day version of musha shugyō.

So, there is a period from the death of Yamada Jirokichi in 1930 and the announcement by Ōnishi after August 1957 where Kawashima is in Taiwan and focusing his efforts on kyudō practice and Ōnishi is first in Hong Kong and then returns to Japan, during which time both men were isolated from other contemporary students of Yamada Jirokichi.

This is not a small break in training during the post-WWII ban on the practice of Japanese martial arts, but rather a long period where Jikishinkage-ryū was fragmented, with its senior adherents attending to more pressing matters than dōjō practice of kenjutsu.

It was known that during the postwar period Kawashima would open ceremonies at the Kashima Jingu hono enbu (martial arts offering), performing aspects of ritual blessing called harai with bow and arrow. Pictures of him without his keikogi show an extremely powerful man – some of the kyudō commentary cited includes descriptions of his pulling a very large bow with only two fingers. While not much is found in English language sources about Kawashima, he is clearly regarded as a senior member of the martial arts community of his time.

One can only wonder what he experienced or what acts he committed that caused him to decline accepting the lineage of one of the most powerful and brutal forms of Japanese swordsmanship from Yamada.

Today many people train in koryū without having learned judo or kendō. At least for Jikishinkage-ryū in the early twentieth century, this was very much not the case. Kendō has since evolved, but it is likely current exponents of the art, not having tested themselves in shiai, practice with a somewhat different mindset than that of Yamada, Kawashima, and Ōnishi, despite their best efforts.

Late 20th Century Masters

After Ōnishi Hidetaka revived his lineage of Jikishinkage-ryū, there is divergence in what different groups claim as the lineage that follows. Ōnishi Hidetaka died in 1963 at the age of 60. His posthumous Buddhist name was Hyakuren-in Shaku Eiryu Koji. Family temple is the Jorinji Temple (6-17-10 Higashiueno, Taito-ku)

The Hyakurenkai was subsequently founded in 1973. Kobudo organizations recognized the Hyakurenkai as the official line of Jikishinkage-ryu Odani-ha, while Kashima Jingu recognized Namiki Yasushi as the next head. The Hyakurenkai maintain that Ōnishi requested Itō Masayuki (1930-2001) be his successor, only for him to leave the Hyakurenkai at the urging of Namiki Yasushi (1926-1999). Both men had trained under Ōnishi and Kawashima – Namiki also trained in Heki-ryu Sekka-ha Kyujutsu under Kawashima; Itō may have as well. Both groups stemming from the Odani faction of Jikishinkage-ryū (i.e., the Hyakurenkai and Namiki’s Hōjōkan) trained it seems mostly separately from 1974 onward.

In Namiki’s case, his death in 1999 left Itō Masayuki in place only for two years as his successor before he too passed away in 2001. In similar fashion possibly to Ōnishi, Yoshida Hijime named himself Itō’s successor and later had a falling out with Namiki’s two adult sons, expelling them from his dojo. They then continued training in Jikishinkage-ryū independent of Yoshida at their own Ku-unkai. Namiki Kazuya continued his practice of kyudō and would wind up demonstrating at events Yoshida’s group also attended – the former presenting bow and the latter presenting sword. I wonder if this was some uneasy truce, or more to do with who kobudo organizations or shrines recognized as being representatives of respective arts.

I had first thought of this quick succession (Namiki to Itō to Yoshida) as a uniquely disruptive event, but looking back on the hundred and twenty-years prior, from the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate to the rise of modern Japan, we see a lineage that is not simply broken but might be more aptly be described as having been shattered. Shattered not in being destroyed but into shards that have then been reworked into different vessels, hopefully with care in the style of pottery woven with silver or gold, retaining its rustic charm. But maybe Jikishinkage-ryū was more of an idea – preserving the methods taught by historical figures of Sakakibara – than an uninterrupted flow through time.

This narrative might not be unique. It might instead point to the idea that modern ideas of ryūha having unbroken lineage or flowing from generation to generation along a single line of transmission, without side interactions, or other knowledge being introduced into a way of practice, as being overly simplistic and idealized. Although there is limited information available, these descriptions from parallel sources (such as kyudō research, in the case of Kawashima’s biography) point to a much more fertile environment than potentially what we see today, with different factions of even a single art only interacting in limited manner, sometimes even within the same line of practice, and with the background of pre-war kendō that is not often examined in koryū circles or writing, due to the subsequent divergence between kendō and kobudō.

Maybe Yamada’s preservation of Jikishinkage-ryū was born out of extremis where the art was in danger of dying out, and Saito Akinobu helped him as a fellow kenshi who practiced the same art. In that way maybe it should be honored and respected, especially if kenshi as strong as Kawashima and Ōnishi resulted from those efforts

Maybe the spirit of Sakakibara’s swordsmanship lived on in those men, even if some had their own demons they sought to tame with the majesty of hōjō swordsmanship.

End Notes

- Mount Kurotaki Fudo-ji Temple

不動寺 1267-1 Oshiozawa,大字 Nammoku, Kanra District, Gunma 370-2801, Japan (5PP2+FC Nammoku, Gunma, Japan) is a location known for its association to Jikishinkage-ryū in the 19th and 20th centuries, centered around it being a location for intense hōjō training sessions. - There are also parallel lines of practice from Ōnishi’s contemporary, Ōmori Sogen (1904-1994), which this essay does not describe. Sogen was closely associated to right wing ultra nationalism during the Japanese 20th century imperial period, in addition to Zen.

- A bibliography containing primary references can be found here.